isaac Mao's List: ToRead

-

-

Even as the processing power and download speeds of mobile devices surge, one component still lags behind: the screen. LCD panels use significantly more power than any other component of a phone or tablet because of their need to pump out bright light to form an image.

The only practical alternative is e-ink, the technology used in the Amazon Kindle; it consumes orders of magnitude less power but sacrifices color and the ability to change images fast enough for video playback or smooth game play.

Now, after years of waiting, alternative technology that promises the best of both approaches is finally edging closer to commercialization. During a recent visit to mobile chipmaker Qualcomm's headquarters in San Diego, Technology Review tried out a full-color, 5.7-inch Android tablet with a display that offers rich colors under bright light, close to those of an LCD and not unlike the pages of a magazine. The prototype screen was also responsive enough for video playback and for a game of Angry Birds; it can deliver up to 30 frames per second.

Because the device's screen uses ambient light, like a printed page or e-ink display, the power consumption is a tenth or less of that of a comparable LCD, although the display also features a built-in light for use in the dark. Known as Mirasol, the technology was created by a startup company, Iridigm, acquired by Qualcomm in 2004.

<!--<p style="clear: both; text-align: center; font-size: 11px; padding:0; margin:0"><a href="#afteradbody" style="text-decoration: none;">Story continues below</a></p>-->

<script type="text/javascript"> <!--//--><![CDATA[//><!-- document.write('<SCR' + 'IPT LANGUAGE="JavaScript" SRC="//ad.doubleclick.net/adj/mk3.technologyreview.com/mediumrectangle4;!category=computingexc;channel=computing;section=;at=mediumrectangle4;page=home;s=mediumrectangle4;dcopt=ist;ord=' + randartnum + '?"><\/SCR' + 'IPT>') //--><!]> </script><script src="//ad.doubleclick.net/adj/mk3.technologyreview.com/mediumrectangle4;%21category=computingexc;channel=computing;section=;at=mediumrectangle4;page=home;s=mediumrectangle4;dcopt=ist;ord=3721448310665727?" language="JavaScript"></script>

"In the market today, you have the iPad at one end and things like e-ink at the other end. This is really meant to bridge both of those worlds," says Clarence Chui, who leads the group at Qualcomm developing the new technology. "It is extremely low power, full color, and can be looked at wherever you go."

The Mirasol display makes color in the same way as the wings of iridescent butterflies or peacock feathers—by being an imperfect mirror that tunes the color of incoming light before reflecting it back to the viewer.

In a Mirasol display, this is done by small cavities known as interferometric modulators, tens of microns across and a few hundred nanometers deep, beneath the display's glass surface. "It's the air gap between the back of that glass and a mirror membrane at the bottom of the modulator that sets the color," says Chui. Each modulator's mirror membrane can snap upward against the glass when a small voltage is applied, closing the cavity and displaying a black color to the viewer. Mirasol modulators are made using techniques similar to those used to pattern metals and deposit materials in computer chip manufacturing.

-

-

-

The equivalent Tea Party network for 15 November, analysing a similar number of tweets posted over about three hours, looks rather different:

(Image: Marc Smith of the Social Media Research Foundation)

Here there are two main clusters, the blue one on the left containing Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul and his supporters. (The diffuse cluster in the lower centre of the diagram consists not of Tea Party supporters, but critics of the movement from the political left.)

-

-

Nov 19, 11

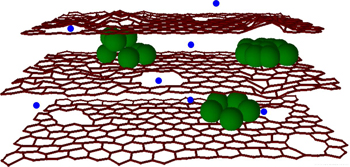

" Clusters of silicon (green) between graphene sheets allow for more lithium atoms (blue) in electrodes for increased charging capacity and nanoholes speed up ion flow for faster charging speed (credit: Northwestern University)

Northwestern University engineers have created an electrode for lithium-ion batteries — rechargeable batteries such as those found in cellphones and iPods — that allows them to hold a charge up to 10 times greater and charge 10 times faster than current batteries; they could also pave the way for more efficient, smaller batteries for electric cars.

The technology could be seen in the marketplace in the next three to five years, the researchers said.

“We have found a way to extend a new lithium-ion battery’s charge life by 10 times,” said Harold H. Kung, professor of chemical and biological engineering.

“Even after 150 charges, which would be one year or more of operation, the battery is still five times more effective than lithium-ion batteries on the market today.”

How Lithium-ion batteries work

Lithium-ion batteries charge through a chemical reaction in which lithium ions are sent between two ends of the battery, the anode and the cathode. As energy in the battery is used, the lithium ions travel from the anode, through the electrolyte, and to the cathode; as the battery is recharged, they travel in the reverse direction.

With current technology, the performance of a lithium-ion battery is limited in two ways. Its energy capacity — how long a battery can maintain its charge — is limited by the charge density, or how many lithium ions can be packed into the anode or cathode. Meanwhile, a battery’s charge rate — the speed at which it recharges — is limited by another factor: the speed at which the lithium ions can make their way from the electrolyte into the anode.

In current rechargeable batteries, the anode — made of layer upon layer of carbon-based graphene sheets — can only accommodate one lithium atom for every six carbon atoms. To increase energy capacity, scientists have previously experimented with replacing the carbon with silicon, as silicon can accommodate much more lithium: four lithium atoms for every silicon atom. However, silicon expands and contracts dramatically in the charging process, causing fragmentation and losing its charge capacity rapidly.

Currently, the speed of a battery’s charge rate is hindered by the shape of the graphene sheets: they are extremely thin — just one carbon atom thick — but by comparison, very long. During the charging process, a lithium ion must travel all the way to the outer edges of the graphene sheet before entering and coming to rest between the sheets. And because it takes so long for lithium to travel to the middle of the graphene sheet, a sort of ionic traffic jam occurs around the edges of the material.

Battery charging breakthroughs

The research team has combined two techniques to combat both these problems. First, to stabilize the silicon in order to maintain maximum charge capacity, they sandwiched clusters of silicon between the graphene sheets. This allowed for a greater number of lithium atoms in the electrode while utilizing the flexibility of graphene sheets to accommodate the volume changes of silicon during use.

The team also used a chemical oxidation process to create miniscule holes (10 to 20 nanometers) in the graphene sheets — termed “in-plane defects” — so the lithium ions would have a “shortcut” into the anode and be stored there by reaction with silicon. This reduced the time it takes the battery to recharge by up to 10 times.

Next, the researchers will begin studying changes in the cathode that could further increase effectiveness of the batteries. They also will look into developing an electrolyte system that will allow the battery to automatically and reversibly shut off at high temperatures — a safety mechanism that could prove vital in electric car applications.

Ref.: Xin Zhao, et al., In-Plane Vacancy-Enabled High-Power Si–Graphene Composite Electrode for Lithium-Ion Batteries, Advanced Energy Materials, 2011; [DOI: 10.1002/aenm.201100426]"-

Clusters of silicon (green) between graphene sheets allow for more lithium atoms (blue) in electrodes for increased charging capacity and nanoholes speed up ion flow for faster charging speed (credit: Northwestern University)

Northwestern University engineers have created an electrode for lithium-ion batteries — rechargeable batteries such as those found in cellphones and iPods — that allows them to hold a charge up to 10 times greater and charge 10 times faster than current batteries; they could also pave the way for more efficient, smaller batteries for electric cars.

The technology could be seen in the marketplace in the next three to five years, the researchers said.

“We have found a way to extend a new lithium-ion battery’s charge life by 10 times,” said Harold H. Kung, professor of chemical and biological engineering.

“Even after 150 charges, which would be one year or more of operation, the battery is still five times more effective than lithium-ion batteries on the market today.”

How Lithium-ion batteries work

Lithium-ion batteries charge through a chemical reaction in which lithium ions are sent between two ends of the battery, the anode and the cathode. As energy in the battery is used, the lithium ions travel from the anode, through the electrolyte, and to the cathode; as the battery is recharged, they travel in the reverse direction.

With current technology, the performance of a lithium-ion battery is limited in two ways. Its energy capacity — how long a battery can maintain its charge — is limited by the charge density, or how many lithium ions can be packed into the anode or cathode. Meanwhile, a battery’s charge rate — the speed at which it recharges — is limited by another factor: the speed at which the lithium ions can make their way from the electrolyte into the anode.

In current rechargeable batteries, the anode — made of layer upon layer of carbon-based graphene sheets — can only accommodate one lithium atom for every six carbon atoms. To increase energy capacity, scientists have previously experimented with replacing the carbon with silicon, as silicon can accommodate much more lithium: four lithium atoms for every silicon atom. However, silicon expands and contracts dramatically in the charging process, causing fragmentation and losing its charge capacity rapidly.

Currently, the speed of a battery’s charge rate is hindered by the shape of the graphene sheets: they are extremely thin — just one carbon atom thick — but by comparison, very long. During the charging process, a lithium ion must travel all the way to the outer edges of the graphene sheet before entering and coming to rest between the sheets. And because it takes so long for lithium to travel to the middle of the graphene sheet, a sort of ionic traffic jam occurs around the edges of the material.

Battery charging breakthroughs

The research team has combined two techniques to combat both these problems. First, to stabilize the silicon in order to maintain maximum charge capacity, they sandwiched clusters of silicon between the graphene sheets. This allowed for a greater number of lithium atoms in the electrode while utilizing the flexibility of graphene sheets to accommodate the volume changes of silicon during use.

The team also used a chemical oxidation process to create miniscule holes (10 to 20 nanometers) in the graphene sheets — termed “in-plane defects” — so the lithium ions would have a “shortcut” into the anode and be stored there by reaction with silicon. This reduced the time it takes the battery to recharge by up to 10 times.

Next, the researchers will begin studying changes in the cathode that could further increase effectiveness of the batteries. They also will look into developing an electrolyte system that will allow the battery to automatically and reversibly shut off at high temperatures — a safety mechanism that could prove vital in electric car applications.

Ref.: Xin Zhao, et al., In-Plane Vacancy-Enabled High-Power Si–Graphene Composite Electrode for Lithium-Ion Batteries, Advanced Energy Materials, 2011; [DOI: 10.1002/aenm.201100426]

-

-

-

- Brain cell activation changes a protein involved in turning genes on and off, suggesting the protein may play a role in brain plasticity.

- Prenatal exposure to amphetamines and alcohol produces abnormal numbers of chromosomes in fetal mouse brains. The findings suggest these abnormal counts may contribute to the developmental defects seen in children exposed to drugs and alcohol in utero.

- Cocaine-induced changes in the brain may be inheritable. Sons of male rats exposed to cocaine are resistant to the rewarding effects of the drug.

- Motherhood protects female mice against some of the negative effects of stress.

- Mice conceived through breeding — but not those conceived through reproductive technologies — show anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors similar to their fathers. The findings call into question how these behaviors are transmitted across generations.

At the Neuroscience 2011 conference, scientists at The Rockefeller University, The Scripps Research Institute, and the University of Pennsylvania presented new research demonstrating the impact that life experiences can have on genes and behavior. The studies examine how such environmental information can be transmitted from one generation to the next — a phenomenon known as epigenetics. This new knowledge could ultimately improve understanding of brain plasticity, the cognitive benefits of motherhood, and how a parent‘s exposure to drugs, alcohol, and stress can alter brain development and behavior in their offspring.

The new findings show that:

-